Last week, speaking at the 11th summit of the Organization of Turkic States (OTS), Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan once again emphasized the importance of adopting a unified alphabet based on the Latin script by the member countries. According to the politician, Turkiye and Azerbaijan are ready for this step, and it would be reasonable for Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkmenistan (which holds observer status in OTS) to support this initiative. Will the post-Soviet republics decide on such sweeping linguistic reforms and what consequences might arise as a result — read below in our article.

Turkish Initiative

The idea of establishing a unified alphabet for all Turkic-speaking countries emerged back in 1991, immediately after the collapse of the USSR. Naturally, Turkey was the initiator of this reform. Notably, this idea was proposed long before the creation of OTS, which only came into existence in 2009 under the name of Turkic Council.

In the 1990s, Turkey played a significant role in the region. For instance, joint Turkish-Uzbekistan lyceums and other educational institutions were opened in Uzbekistan, where Turkish language studies were actively pursued. Foreign businessmen opened previously unseen supermarkets and large shopping centers in Tashkent. Even TV series produced on the shores of the Bosporus quickly gained popularity.

But let's go back to the alphabet. The process of creating a unified set of letters picked up momentum a few years ago when a special commission was formed within the Organization of Turkic States. This commission included two representatives from each of the five member countries.

Unified Turkic Alphabet

September of this year, the third meeting of the Commission on a Unified Alphabet for the Turkic World was held in Baku, where experts announced that all interested parties had agreed on the project.

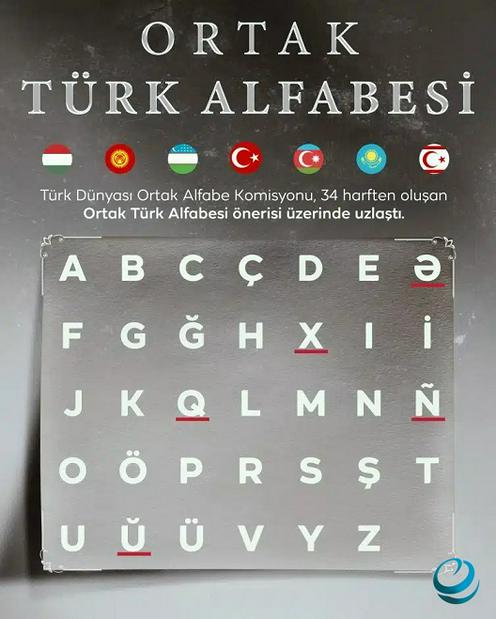

«As a result of this dedicated work, an agreement was reached on a proposal for a unified Turkic alphabet consisting of 34 letters. Each letter in the proposed alphabet represents different phonemes of Turkic languages,» stated an official press release. At the same time, experts emphasized that while creating a common alphabet, they tried to preserve the linguistic heritage of each nation individually.

The alphabet consists of 34 letters. Alongside familiar Latin letters A, B, C, there are original ones with diacritical marks such as Ň or Ŭ. An important detail: The modern Turkish alphabet has 29 letters, meaning that five more will be added during unification. Therefore, Ankara is ready to make «sacrifices» in terms of expenses related to changing educational programs, documentation, road signs, etc., for the sake of implementing this large-scale reform.

Azerbaijan, which switched to Latin script back in 1991, will also have to adjust since its current alphabet consists of 32 symbols. As for other OTS countries—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and even Uzbekistan—they still use Cyrillic.

A year ago, Erdogan argued that a unified alphabet is necessary for OTS members to stay together and face challenges efficiently. Now at the summit in Bishkek, he stated that a unified alphabet is «a sign that we are building our future together."

Attempt No…?

Are former Soviet republics ready to «build their future» under the influence of their, to call it straight, «big Turkish brother»?

Kyrgyzstan seems to face the most difficulty. First off, there hasn't been much consideration given to switching to Latin script in this country yet. The 36-letter alphabet currently used is essentially a variant of Russian with three additional symbols representing unique Kyrgyz sounds. Secondly, besides Kyrgyz as the state language, Russian also holds official status here by law and is used to duplicate most documents. This clearly indicates Russia's influence—a factor Moscow is unlikely willing to lose. Thirdly, Kyrgyzstan recently updated its national flag by straightening sun rays and making other cosmetic changes. Although authorities claimed that sponsors would cover most costs associated with changing symbols, some expenses still came from state funds. Now there's another looming fundamental reform—the alphabet—which may be too much for Kyrgyzstan's budget to handle.

Kazakhstanis today use a Cyrillic script consisting of 42 letters, in use since 1940. But already in the 21st century, the country's first president Nursultan Nazarbayev decided to switch to the Latin alphabet — as political scientists said, primarily to reduce dependence on the country’s northern neighbor, Russia. In 2017, the head of state even approved a new version of the alphabet, consisting of 31 symbols. However, it was immediately indicated that the radical reform would take time — a phased transition was planned until 2025. Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, who replaced Nazarbayev, showed even more caution, constantly urging officials not to rush with the Latin alphabet to avoid mistakes. Thus, the process was pushed back for another six years, until 2031. And here is the Turkish initiative. Will Kazakhstan hurry in this matter? Unlikely.

Technically, it is easier for Uzbekistan to adopt a unified Turkic alphabet than for others, as it has long implemented the Latin alphabet and currently uses two versions of writing. The first leader of the republic, Islam Karimov, signed the decree back in 1993. The Turkish version was taken as a basis. But gradually the authorities began to conflict with the Turks: in particular, foreign investors complained about «raider seizures» of businesses by local security forces and other figures who had support from above.

The situation was reflected in the alphabet, which shifted towards English, it included letter combinations «ch» and «sh» denoting corresponding sounds. In total, the set has 29 symbols, including letter combinations, and an apostrophe in the role of a hard sign.

Despite decrees requiring more frequent use of the Latin alphabet, it has not really taken root in the republic. Moreover, experiments continue. For example, under the new head of state Shavkat Mirziyoyev, it was decided to replace English letters with those inherent in the Turkish alphabet. For example, to graphically denote «ch» and «sh», it is proposed to return the variants »ç» and »ş».

This reform has been discussed for many years. In fact, the country is divided into two camps: young people under 35 prefer the Latin alphabet, while older people do not want to give up the familiar Cyrillic and sometimes cannot even read inscriptions in their native language, but in a new form.

It is safe to say that Uzbekistan will be able to change its Latin alphabet to a single Turkic template with the least pain. Especially while maintaining double writing, as it is now.

Utopia or reality?

This is not the first time Central Asia is switching to another alphabet. Before the revolution of 1917, when the Bolsheviks began to build the Soviet Union, Arabic script was used in this region. In the mid-1920s, it was decided to use the Latin alphabet for all Turkic languages. They began to implement the new order from 1930, but ten years later, in order to unify the graphics for a single state, all the peoples of the USSR began to master the Cyrillic alphabet.

These fluctuations were more or less painless, because then the majority of the population consisted of illiterate people, that is, they learned the new alphabet from scratch. Today it's a different matter. And the example of Uzbekistan, which has been switching to the Latin alphabet for more than 30 years, but cannot abandon Cyrillic, demonstrates the complexity of the reform.

I will give an example from the life of my friend. In 2007, he traveled all over Uzbekistan for work, twice. Back then, the periphery had already almost universally switched to the Latin alphabet (Islam Karimov set the task for officials to completely Latinize the country by 2020). My friend, Russian by nationality, but fluent in English, faced a paradox. His driver, a 33-year-old Tashkent resident without higher education, could not read the signs, he did not even know new letters, although Uzbek is his native language, and he spoke it.

In case a common Turkic alphabet is imposed on almost all post-Soviet republics of the region, situations like this will keep happening. Add here new expenses, because it will be necessary to rewrite textbooks, school curriculum, road signs, passports, and other documentation.

Another point is how the new Latin alphabet will affect labor migrants. After all, the main direction for them is Russia, and the situation is unlikely to change in this regard in the coming years. Arrivals from Central Asia, especially young people, are already facing problems not knowing the Russian language. Meanwhile, Moscow is imposing more and more strict requirements, including language proficiency: if you didn't pass the exam, you go back. In the long run, the introduction of the Latin alphabet can lead to the emergence of generations who cannot read and write in Cyrillic. And how can they work in the Russian Federation? After all, there are more than a million Uzbeks alone in Russia. Of course, one can consider other destinations for labor migration, but perhaps there is no other state capable of employing such a number of citizens of the Central Asian region.

A unified alphabet or even language in Central Asia has been discussed before. In 2007, in a comment to Fergana, Doctor of Historical Sciences, Professor Goga Khidoyatov called the proposal to create a common Turkic language «delusional ideas of pan-Turkists».

«There can be no common Turkic language! I believe this is utopia. Azerbaijanis have their own — Nizami, we have Navoi, let's say, Xinjiang has its own authors, its own traditions, how can they be combined? It's as if tomorrow, let's say, we decide and create a common Slavic language,» Khidoyatov summed up.

In conclusion, let's return to the summit of the Organization of Turkic States, held in Bishkek last week. Among the documents signed by the parties, there is a memorandum of understanding regarding the development of the Great Turkic Language Model of the OTS. This document could contain clauses on creating a unified alphabet. But there is sometimes a long way from intentions to real actions, especially if it concerns language. And Turkish leader Erdogan will still have to make a lot of effort to persuade neighbors to accept his initiative.

-

14 February14.02Make Central Asia…How U.S. President Donald Trump's Policies Will Affect the Region

14 February14.02Make Central Asia…How U.S. President Donald Trump's Policies Will Affect the Region -

28 December28.12Are Birds Really to Blame?Exploring the Theories Behind the Azerbaijan Airlines Plane Crash in Kazakhstan

28 December28.12Are Birds Really to Blame?Exploring the Theories Behind the Azerbaijan Airlines Plane Crash in Kazakhstan -

25 December25.12Passenger Plane Crashes in Kazakhstan — Latest Updates

25 December25.12Passenger Plane Crashes in Kazakhstan — Latest Updates -

18 November18.11Land of Turks is Not for TurksDid Turkey Have Chances to Gain Power Over Central Asia

18 November18.11Land of Turks is Not for TurksDid Turkey Have Chances to Gain Power Over Central Asia -

13 September13.09Kazakhstan's Nuclear DilemmaReferendum Raises Questions

13 September13.09Kazakhstan's Nuclear DilemmaReferendum Raises Questions -

06 August06.08What went wrong in Central Asia’s coronavirus response?How poor planning and a fixation on faulty test results undid months of hard work

06 August06.08What went wrong in Central Asia’s coronavirus response?How poor planning and a fixation on faulty test results undid months of hard work